Kader Attia - Archeology of modernism

I think that the big failure of modernism is that justifying any kind of experimentation that aimed to perfection, it has actually built utopias and the world we are living in is utopian more and more...what we missed in modernism is our identity. [Kader Attia]

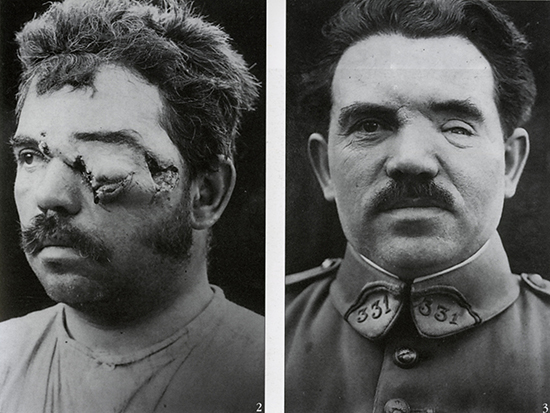

Kader Attia, Open your eyes, slide show, 2010, ph. M. Monestier, courtesy Galleria Continua.

Kader Attia (b. 1970, France), lives and works in Berlin and Algiers. He grew up in both Algeria and the suburbs of Paris, and uses this experience of living as a part of two cultures as a starting point to develop a dynamic practice that reflects on aesthetics and ethics of different cultures. He takes a poetic and symbolic approach to exploring the wide-ranging repercussions of Western modern cultural hegemony and colonialism on non-Western cultures, investigating identity politics of historical and colonial eras, from Tradition to Modernity, in the light of our globalized world, of which he creates a genealogy.

Kader Attia, Holy Land, mirrors, 2007-2013, ph. Ela Bialkowska, courtesy Galleria Continua

Taking cue from the relocation of his mirror-based installation Holy Land, whose pristine venue was a Canarian shore and it is now on view at the Galleria Continua, we talked about site-specificity: what does remain of the seemingly binding link between the work and that site? what are the new meanings involved in the translation of the work in this clichéd spot of Tuscany?

Holy Land was also the pretext to talk about "the sacred": architectural displays of it - as also of political power and in general all those iconic buildings whose reading is strongly informed by history and whose imaginary is handed on by media and pop culture - are very much questioned by the artist.

In The History of a Mith. The small dome of the rock - a video projection produced for the 2010 Abraaj Capital Prize - Attia assembled two bolts, two little and humble bolts; this assemblage is anything but a miniature sculpture resembling the image of the Dome of the Rock, the well known bone of contention between Jews and Arabs in Jerusalem. He then enlarged the little sculpture through a live camera, magnifying and projecting the image on the wall. More than a political work, he tells us, it is a way to break the icon, to reappropriate this marvellous architecture behind history, western political perception of it and behind popular mithology.

Still architecture is not just about history; we could say that whilst the public and political dimension of architecture is strongly filtered through the lens of history, the value of the same architecture is strongly associated to memory when we enter the private sphere of those whose life has been informed by that architecture. In many countries, for instance, social housing is undergoing massive State driven demolitions and if a demolition is a political attempted full stop in the narration of modernist social utopias, it is also often bathed in tears.

Moreover, ugliness - that is one of the most common given causes behind western demolitions - in architecture is a shifty notion and can't be just a prejudice of value - that is an aesthetic one above all - because it is also bound to the idea of functionality.

The poorer is the house the more functional it is, that means that what seemed to be a modernist and western idea, functionality, is rather a natural force that has driven as Le Courbusier's practice as many improvised architects all around the globe and has shaped even the poorest European shanty towns and the most alien and distant villages in Africa.

Many architects, among those Attia quotes Roland Simounet, found in Algeria and in African vernacular architecture some very interesting evidences of this common ground of research in terms of functionality. It is not legendary but supported by many scholars and documents for instance, how Le Courbusier was deeply aware of Algerian region La Ghardaia, where he spent time, studying, photographing, where - in a very tough environment he found perfect examples of functional aesthetics, the roof terrace, the free walls, architectural features that didn't exist in western world before his trip. How did he know Ghardaia? Thanks to The urban civilization of M'Zab a book by Marcel Mercier that, in a way, christened the modernist strand in architecture.

Kader Attia, in his attempt at understand the archeology of modernism, at showing that culture is not one way, recurs to the notions of UNIVERSALITIES, in plural terms, of REAPPROPRIATION and TRANSLATION. In this interview he explains us how he combines images of the first plastic surgery experimentation in the post first world war and some pictures of african broken pottery and sculpture. On one hand the goal of perfection, on the other the aestetic of the repair.

The music that goes with the interview is selected from the albums Paranormal is the Normal and Taciturn by Nic Bommarito, both downloadable at www.12rec.net/.